A dalek spacecraft from the film “Daleks’ Invasion of Earth: 2150AD”

Watch…

Things to Come (1936)

The film is based on H G Wells’s novel The Shape of Things to Come (1933) in which he imagined a future history of the world, beginning with a world war in 1940 which destroys much of civilisation. After societal collapse humanity is eventually rescued by a group of aviators. The film version (which Wells assisted) was produced by Alexander Korda, directed by William Cameron Menzies, and starred Ramond Massey, Ralph Richardson, Cedric Hardwicke, Pearl Argyle and Margaretta Scott.

You can watch the film here.

You can read Wells’ novel here.

The Thing From Another World (1951)

The film was based on the 1938 novella Who Goes There by John W Campbell. An American base in the Arctic discovers something buried in the ice – and someone. The scene in which the exploring party members spread out across the ice – and realise what they have found is a classic. The film ends with an urgent appeal: “Watch the Skies!”

You can watch it here.

X The Unknown (1957)

An early Hammer film in which a prehistoric radioactive substance emerges from out of the earth causing death and destruction in its mindless pursuit of radioactive sources to feed itself. It was produced by Anthony Hinds, written by Jiimmy Sangster and directed by Leslie Norman and Jospeh Losey. The cast included Dean Jagger, Leo McKern and Edward Chapman – and a cameo from youthful Frasier Hines.

You watch the film here

The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961)

One of the best British science fiction films of the 1960s, directed by Val Guest. Simultaneous nuclear explosions by the USA and USSR send the Earth out its orbit and towards the Sun. Only another explosion may perhaps save the world. The story is told through the eyes of Peter Stenning (Edward Judd), a reporter on the Daily Express. The film include scenes in the newpsaper’s offices and also makes extensive use of London locations.

You can watch the film here.

A for Andromeda (1961)

This series was created by Fred Hoyle and John Elliot. The plot involves a radio telescope receiving a signal and data from the direction of the Andromeda galaxy which enables scientists to create a computer and then life, a young woman they call Andromeda. But who is she and what is her real mssion? The cast included Peter Halliday, Mary Morris, Julie Christie and John Hollis. Sadly only the penultimate episode “The Face of the Tiger” has survived in its entirety.

You can watch “The Face of the Tiger” here.

You can read my post on the series here.

The Andromeda Breakthrough (1962)

Due to the success of A For Andromeda the BBC quickly commissioned a six part sequel. As the BBC had failed to offer a Julie Christie in time, the part of Andromeda was now played by Susan Hampshire. Peter Halliday, Mary Morris and John Hollis reprised their roles, joined by Claude Farell and Barry Linehan. You can read my post on the series here. The first four episodes are available on Daily Motion:

These are the Damned (1963)

A British film directed by Joseph Losey and starring Sally Ann Field, Macdonald Casey and Oliver Reed. Hoilday makers at the seaside discover a group of children hidden away in a secret government bunker who, owing to an accident are resistant to nuclear radiation.

You can watch the film here.

The Stranger (1964, 1965)

An Australian science fiction children’s television series written by G K Saunders and produced by ABC. In the middle of a rain storm a stranger arrives on the dootstep of a family claiming to have lost his memory. Who is he? Where has he come from ? What does he really want? The stranger was played by Ron Haddrick who lifts the series out of the ordinary. He went on to become one of Australia’s best known actors. The series sold well abroad: I watched it on the BBC in 1965.

You can watch the series here.

UFO (1970)

This live action series c was reated by Sylvia and Gerry Anderson (creators of Stingray, Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet etc). It follows the exploits of a secret organisation called SHADO set up to fight attacks by alien spacecraft. It’s set in 1980 by the way. Odd that the purple wigs never happened. Only one series of 26 episodes was made.

You can watch the series here.

Space 1999 (1975-1977)

A massive explosion on the Moon sends it out of orbit on 13th September 1999 and on a journey across the galaxy. The inhabitants of Moonbase Alpha meet a variety of aliens along the way – some friendly, some not, of course. The series was created by Sylvia and Gerry Anderson. Two series were made.

You can watch series 1 here.

You can watch series 2 here.

Children of the Stones (1977)

Astrophysicist Adam Brake (Gareth Thomas) and his young son Matthew (Peter Demin) arrive in the small village of Milbury, which is built in the midst of a megalithic stone circle. Increasingly strange phenomenon are happening, while many of the villagers are in thrall to a cult, the “Happy Ones.” The series was filmed in Avebury.

You can watch the series here.

The Day of the Triffids (1981)

A BBC dramatisation of the novel by John Wyndham, which is by far the best version, scripted by Douglas Livingstone. The cast includes John Duttine, Emma Relph and Maurice Colbourne.

Bill Masen is in hospital, having suffered a minor eye injury and awaiting the removal of his bandages. He calls repeatedly, but nobody comes. Plucking up the courage to take off the bandages, and venturing on to the streets of London, he discovers that most of the world has gone blind overnight, apparently after watching a metor shower. Can humanity survive this catastrophe?

Other than updating it to the 1980s the producers sensibly left the plot intact. You can read my post on the novel here.

You can watch the six episodes as follows

Blakes 7 (1978-1981)

Created by Terry Nation this BBC series ran for four seasons. In the far future a group of resistance fighters led by Blake (Gareth Thomas) and later Avon (Paul Darrow) take on the oprressive Federation. Their chief opponent is the effortlessly cool and unfailingly evil Servalan (Jacqueline Peace)

You watch the series here.

Quatermass IV (1979)

Often overlooked, the conclusion to the Quatermass series. The four episode series was written by Nigel Kneale, of course, and starred John Mills as Bernard Quatermass.

It is set in a near future in which large numbers of young people are joining a cult, the Planet People, and gathering at prehistoric sites, believing they will be transported to a better life on another planet. Professor Quatermass arrives in London to look for his granddaughter, Hettie Carlson, and witnesses the destruction of two spacecraft and the disappearance of a group of Planet People at a stone circle by an unknown force.

You watch the series here

The Lathe of Heaven (1980)

I dream. You dream. We all dream. Every night. And then forget them. Mostly. But suppose our dreams came true? This is the intriguing premise of Ursula Le Guin’s 1971 novel which follows the dreams and story of an ordinary man George Orr with an ordinary job living in an ordinary flat who has an extraordinary ability. The Lathe of Heaven was made into a television movie in 1980 by WNET and starred Bruce Davison, Kevin Conway, and Margaret Avery.

You can watch the film here.

You read my post on the novel here.

Chocky (1984)

A Thames television series, based on John Wyndham’s last novel, and written by Anthony Read. Matthew is 12 and has an imaginary friend called Chocky whom he insists is real to the increasing alarm of his parents. But just how imaginary is Chocky? The cast includes James Hazeldine, Carol Drinkwater and Andrw Ellams.

You can watch the series here.

It was followed by two sequels, not based on the book, but using some of the the same characters.

Chocky’s Children (1985) which you can watch here

Chocky’s Challenge (1986) which you can watch here.

Listen…

The Time Machine by H G Wells (1895)

One of the novels in the 1890s in which Wells invented modern science fiction. The story of an unnamed scientist whose time machine takes him far into the distant future, AD 802701. Here humanity has evolved into the Eloi, childlike creatures who live on fruits and whose simple life seems idyllic. But this Eden has serpents. The traveller discovers that in the depths underground there are other, darker, creatures..

The Time Machine was dramatised on the radion by the BBC in 2009. The cast included Robert Glenister , William Gaunt, Jill Cardo and Dan Starkey.

You can listen to this broadcast here.

The War of the Worlds radio broadcast, 1938

On 30th Ocober 1938 the Mercury Theatre on the Air made a radio broadcast on Columbia Radio of the H G Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1897), adapted and directed by Orson Welles, who transferred the story to contemporray USA. After an inital announcement music was played for half an hour until it interrupted by a newsflash announcing that a projectile had fallen in New Jersey. Then the story is carried forward with a series of dramatic news bulletins and vivid outside broadcasts describing the Martians emerging from the cylinder and then using a heat ray. The first half of the broadcast ends with a reporter on a skyscraper describing New York being enveloped by black poisonous gas.

Some listeners, who had missed the start of the broadcast, believed that what they were hearing was real and there was a panic in some parts of the East Coast, but not as much as the myths about the broadcast might have you believe.

You can listen to the broadcast here.

This is an article about the broadcast.

The Invisible Man by H G Wells (1897)

The novel begins with a mysterious traveller staying in an Inn In West Sussex whose actions and appearance increasingly draw suspicion from the locals. Who is he? And why does he conceal his face?

You can listen to a dramatisation starring John Hurt here.

1984 by George Orwell (1949)

One of the most influential and pessimistic novels of the twentieth century, It is set in a socialist England (EngSoc) (now called Airsrip One) in which the citizens are controlled and surveyed at all times by an all powerful state headed by Big Brother. The Ministry of Peace, Ministry of Plenty, Ministry of Love and Ministry of Truth are the chief organs of the state. Winston Smith attempts his own personal revolt. Can he succeed?

It was dramatised for the radio by the BBC in 1965. The cast included Patrick Troughton. You can listen to this here.

The Kraken Wakes by John Wyndham (1953)

In his second novel The Kraken Wakes John Wyndham again imagines the breakdown of human civilisation, but in a very different way and from a very different kind of menace. By contrast with The Day of the Triffids – in which the Triffids were home-grown destroyers and highly visible throughout the novel – in The Kraken Wakes the invaders appear to be from another planet, and are almost never seen, having based themselves in the ocean deeps.

In 1998 the BBC broadcast an adaptation by John Constable. Michael Watson was played by Jonathan Cake, Phyllis Watson was played by Saira Todd. You can listen to the series here.

In 2004 the BBC broadcast a reading of the novel in 16 parts, read by Stephen Moore. You can listen to this here.

The Caves of Steel by Isaac Asimov (1954)

Set in a future in which most of humanity is packed into “caves of steel” – huge underground cities – the novel is a murder mystery. Detective Elijah Bailey, who has been given the task of finding out who murdered a Spacer ambassador, is assigned a robot – R Daneel Olivaw – as his partner, much to his horror.

Thel novel was dramatised in 1989 by the BBC, adapted by Bert Coules. The cast included Ed Bishop, Sam Dastor and Matt Zimmermann.

You can listen to this here.

The Chrysalids by John Wyndham (1955)

The novel set in the future, perhaps several centuries after our own time. The story is told through the eyes of David Strorm as he grows up in a rural part of Labrador. This is a religiously fundamentalist society, fearful of any kind of physical difference in human bodies. “Watch Thou For The Mutant!”is drummed into the population. . We, the readers, soon divine that the “Tribulation” of which they talk was in fact a nuclear war, and that this is the society that has somehow survived, plunged back into a subsistence way of life, based on farming, with no technology. But within this ossified society the seeds of a new kind of human being are emerging into the light. In my opinion this is John Wyndham’s masterpiece.

The novel was dramatised by the BBC in 1981 in an adapation by Barbara Clegg. The cast included Stephen Garlick, Amanda Murray. Judy Bennett and Jane Knowles. You can listen to the series here

You can read my post on the book here.

The Midwich Cuckoos by John Wyndham (1957)

The story begins with a small ordinary English village being subject to a mysterious force rendering everyone within a circle unconscious for a whole day on Tuesday . The authorities outside cannot get in: an aerial photograph reveals an object in the village with “a pale oval outline, with a shape, judging by the shadows, not unlike the inverted bowl of a spoon.” When the village come back to life the object has gone, while the villagers appear not to have been harmed by what they quickly come to call “the Dayout”.

Some months later, however, every woman of childbearing age, married or single, discovers that she is pregnant. When the children are born they have golden eyes and, as they grow up, reveal disquieting powers. Who are they and what is their real mission?

The novel was adapted by William Ingram for the BBC World Service in 1982. The cast included Charles Kay, William Gaun , Manning Wilson and Pauline Yates.

You can listen to the radio series here.

You can read my post on the novel here.

The Slide by Victor Pemberton (1966)

A chilling seven part radio series in which a small seaside town is menaced by an eruption of sentient mud which seems to have a mental hold on some of the inhabitants. I listened to The Slide when it was broadcast, aged 11, and it left a vivid impression on me. When I listened again more than 40 years later, I thought it was still very effective.

The cast included Roger Delgado, Maurice Denham, David Spenser and Miriam Margolyes. The producer was John Tydeman and the sound effects were, of course, by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Victor Pemberton also wrote the Doctor Who serial “Fury from the Deep” (1968).

You can listen to the series here.

The Dispossesd by Ursula Le Guin (1974)

In her new introduction to the Library of America reprint in 2017, Ursula wrote:

“The Dispossessed started as a very bad short story, which I didn’t try to finish but couldn’t quite let go. There was a book in it, and I knew it, but the book had to wait for me to learn what I was writing about and how to write about it. I needed to understand my own passionate opposition to the war that we were, endlessly it seemed, waging in Vietnam, and endlessly protesting at home. If I had known then that my country would continue making aggressive wars for the rest of my life, I might have had less energy for protesting that one. But, knowing only that I didn’t want to study war no more, I studied peace. I started by reading a whole mess of utopias and learning something about pacifism and Gandhi and nonviolent resistance. This led me to the nonviolent anarchist writers such as Peter Kropotkin and Paul Goodman. With them I felt a great, immediate affinity. They made sense to me in the way Lao Tzu did. They enabled me to think about war, peace, politics, how we govern one another and ourselves, the value of failure, and the strength of what is weak.

So, when I realised that nobody had yet written an anarchist utopia, I finally began to see what my book might be. And I found that its principal character, whom I’d first glimpsed in the original misbegotten story, was alive and well—my guide to Anarres.”

You can listen to a dramatisation of this novel by CBC radio here.

Short Stories by Ken Macleod

The Entire Immense Superstructure’: An Installation

Read…

From the Earth to the Moon by Jules Verne (1865)

Jules Verne invented a good deal of what later came to be called “science fiction,” his work was widely read not just in France but in Anglophone countries as well. In this early novel the Baltimore Gun Club decide to visit the Moon, not using a rocket, but instead by building a huge gun In Florida and firing a shell towards our satellite.- with themselves inside ! The novel was adapted as the opera in 1875, with music by Offenbach. It also inspired the first science fiction film A Trip to the Moon.

You can read the novel here.

You can read the sequel All Around The Moon (1870) (and find out if the three adventurers survived the trip) here.

You can watch A Trip to the Moon here.

20,000 Leagues under Sea by Jules Verne (1871)

Three adventurers in pursuit of what is though to be a giant narwhal which has been attacking shipping discover it is in fact an electric powered submarine and are taken aboard. Commanded by Captain Nemo, the Nautilus roams the world’s occens gathering scientific knowledge but also attacking ship in a personal vendetta by Nemo. it has been filmed several times.

You can read the novel here.

You can read the sequel The Mysterious Island here.

You can watch the 1916 silent film of the novel here.

When The Sleeper Awakes by H G Wells (1898)

Graham wakes up after being asleep for 203 years, having fallen into a coma at the end of the C19th. Whilst asleep he has not only became a symbol of hope for the common people, but also, because of the investments made in his name by his friends, which have grown enormously during his time asleep, he is actually “the Owner” – the Master of the world. The moment he wakes up, he is plunged into the midst of a revolution as the people, led by Boss Ostrog, battle and defeat the oppressive White Council, which was ruling the world in his name. The rest of the novel follows his adventures in this future society, whose real nature he only slowly comes to comprehend.

You can read the novel here.

You can read my post on the novel here.

The Sorcery Shop: an Impossible Romance by Robert Blatchford (1907)

In The Sorcery Shop Robert Blatchford attempts to describe what a Socialist utopia might look like, imagining the grimy, smoke-clogged city of Manchester, which he knew very well, transformed a sunlit city of flowers, fountains and crystal towers. It is of a piece, therefore, with other socialist utopian novels of the period, including Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888), William Morris’ News from Nowhere (1890), H G Wells’ A Modern Utopia (1905) and Men Like Gods (1923), and Charlote Perkins Gilman’s Herland (1915)

Robert Blatchford and his friends were the founders in 1891 of the Clarion newspaper: the most influential Socialist newspaper ever published in Britain, which created thousands of Socialists and inspired a whole social movement.

You can read the novel here.

You can read my post on the novel here.

October the First is Too Late by Fred Hoyle (1966)

In his introduction to this novel Hoyle writes: “The ‘science’ in this book is mostly scaffolding for the story, story-telling in the traditional sense. However, the discussions of the significance of time and of the meaning of consciousness are intended to be quite serious…”

Hoyle’s novels often have a scientist as the main protagonist, but in this novel it is a musician and composer named Dick: accordingly each chapter is named after a musical theme or style eg “Fugue” and “Coda.”. The novel begins in 1966 when he runs into an old university friend John Sinclair, now a scientist, and on an impulse they set off together on a trip to Scotland. Something very odd happens here. Sinclair disappears for half a day, and on returning cannot explain or recall what has happened to him. The trip is cut short when Sinclair is recalled to the USA to assist in the investigation of a strange solar phemonena. Dick accompanies him to Hawaii, where Sinclair and others establish that the Sun is somehow being used as a signalling device with an enormous amount of data being transmitted. Barely have they absorbed this astonishing fact when all contact is lost with the USA: it is feared that a nuclear war has begun.

Dick and Sinclair manage to get places on a plane sent to investigate what has happened. Flying above Los Angeles there is no sign of a war: the city is simply no longer there, just woods and grassland in its place. Journeying on, they see the same across the continent. Crossing the Atlantic they find to their relief that the England of 1966 is still there but Europe has reverted to 1917 with the First World War raging. The rest of the novel explores the implications and possible cause of this extraordinary situation. .

You can read the novel online here.

You can read my post on the novel here.

Mutant 59: the Plastic Eater by Gerry Davis and Kit Pedler (1972)

Gerry Davis and Kit Pedler met in 1966 when Gerry was the script editor at Doctor Who, and was looking for a scientific advisor to inject a greater degree of scientific speculation into the programme. Kit was head of a research unit at the Institute of Opthamalmology at the University of London.

Kit suggested that the newly built Post Office Tower, then the tallest structure in London, could be used by a computer to take over the capital using the telephone network to control the minds of humans. This evolved into the serial The War Machines, broadcast in the summer of 1966, featuring the computer WOTAN and its war machines. They then came up with the idea of the Cybermen: humanoids who have replaced so much of their bodies with technology that they have lost all emotion and empathy. Their first story featuring the Cybermen “The Tenth Planet” aired in the autumn 1966. The silver monsters were a big hit with the public, and were quickly brought back in “The Moonbase” (February 1967) and then in “The Tomb of the Cybermen” (September 1967). After Gerry left Doctor Who Kit worked with Victor Pemberton on “The Wheel in Space” (May 1968), and with Derrick Sherwin on another Cybermen serial “The Invasion” (November 1968). This was Kit’s last involvement with Doctor Who.

By 1970 Kit was becoming disillusioned by science and increasingly alarmed about the effect that technology and the headlong rush for economic growth at all costs was having on the environment. He, and many others around the globe, feared the possibility of ecological collapse. Working together again, Kit and Gerry created a series for the BBC called Doomwatch. “Doomwatch” is the nickname for special government unit established to monitor environmental and other threats to the public. The first series created a sensation with storylines on issues such as transplants, genetic mutation of rats, chemical poisoning, and a crashed nuclear bomb on the south coast. The extensive scientific research done by Kit for the series meant that the storylines appeared to anticipate news stories.

After Doomwatch Gerry and Kit wrote three novels together, the first of which was Mutant 59, partly based on a storyline in Doomwatch.

You can read the novel here.

You can read my post on the novel here.

You can read a 1973 interview with Gerry and Kit here.

You can read my post on their second novel Brainrack (1974) here.

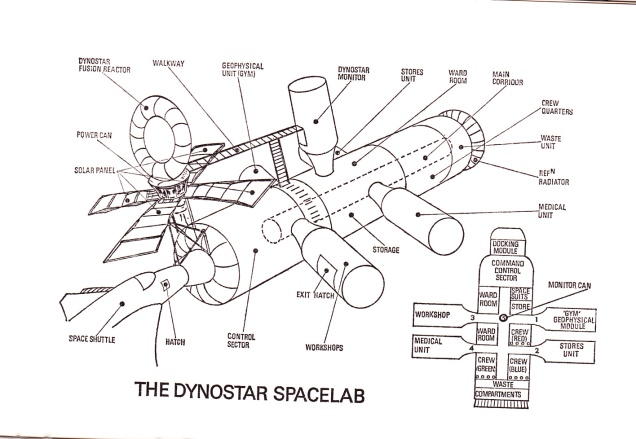

You can read my post on their third novel The Dynostar Menace (1975) here.

The Exile In Waiting by Vonda N McIntyre (1975)

The novel is set on a future Earth, turned into a desert by some environmental catastrophe. The only surviving city is Center, an underground city run by a handful of wealthy families who control the air, food, power and water. Many of the inhabitants are little more than slave in thrall to the familiess.

Mischa is a teenager, scraping a living in the back streets of Center by any means possible, including stealing. She is also an empath who senses the moods of others, including her sister Gemmi with whom she has a strong emotional link that keeps her trapped in Center. The novel follows her quest for freedom and happiness.

You can read the novel here.

You can read my post on the novel here.

Dreamsnake by Vonda N McIntyre (1978)

The novel seems to be set in the world outside Center. Snake is a healer who uses her three snakes to cure people. But her very rare dreamsnake is killed and she needs to find another. The novel follows her quest and her adventures and encounters on the journey.

You can read the novel here.

Superluminal by Vonda McIntyre (1983)

Often overshadowed by Vonda’s first two novel. Laenea Trevelyan, has her heart replaced with a machine so she can survive faster-than-light travel and become a pilot. Orca, a diver, divides her time between starships and the Strait of Georgia, where her relatives include a family of killer whales and a group of other divers, human beings who can exist underwater. Radu Dracul, a colonist from the alien world Twilight, having chosen to leave his home and become a starship crew member, discovers he has abilities he never dreamed of…

You can read the novel here.

Short Stories by Ken Macleod

Learn…

Andrew Pixley

For the last 30 years Andrew has written about almost anything to do with television if people will pay him – and occasionally when they won’t… He has made many contributions to the Doctor Who magazine, worked as a consultant and researcher on tv documentaries such as Thirty Years in the Tardis, written The Avengers Files and The Daleks; a history from BBC Video, as well providing the accompanying notes to a variety of boxsets of televison and radio series, including Doctor Who, A for Andromeda, Callan, Public Eye, The Prisoner and Journey into Space.

You can read his posts on the Critical Studies in Television blog here

A podcast about Nigel Kneale and the Quatermass series.

Blogtor Who :the definite article you might say.

Extensive news and resources site on Doctor Who, Big Finish releases. etc.

The official BBC site with many resources on the series, past and present

The Early Days of a Better Nation

Science fiction Ken Macleodreflects on science fiction, socilaist politics and much else. the title comes from two sources: “Work as if you lived in the early days of a better nation.”—Alasdair Gray. “If these are the early days of a better nation, there must be hope, and a hope of peace is as good as any, and far better than a hollow hoarding greed or the dry lies of an aweless god.”—Graydon Saunders

Encyclopedia of Science Fiction.

Now in its third edition, edited by John Clute, David Langford, Peter Nicholls (emeritus) and Graham Sleight (managing). It has more than 18,000 entries which are free to read online.

Galactic Journey. 55 years ago science fact and fiction

The website looks back 55 years to another world, another time, with sections on science fiction, music and much more from 1965.

The H.G. Wells Society was founded by Dr. John Hammond in 1960. It has an international membership, and aims to promote a widespread interest in the life, work and thought of Herbert George Wells. The society publishes a peer-reviewed annual journal, The Wellsian, and issues a biannual newsletter. It has published a comprehensive bibliography of Wells’s published works, and other publications, including a number of works by Wells which have been out of print for many years.

K U Gunn Centre for the Study of Science Fiction

This site provides a wealth of information and informed commentary about science fiction and the Center’s programs, including awards, course syllabi, writing resources, and much more.

Merril Collection of Science Fiction, Speculation and Fantasy

A non-circulating research collection of over 80,000 items of science fiction, fantasy and speculative fiction, as well as magic realism, experimental writing and some materials in ‘fringe’ areas such as parapsychology, UFOs, Atlantean legends etc.

“A blog for all Doctor Who fans, ran by female Doctor Who fans.”

In honour of the 50th anniversary of Doctor Who in 2013, Toby Hadoke embarked on an epic quest: to interview someone from every single Doctor Who story. Feeling Doctors or companions are a bit too easy, he travels the country meeting legends from the show’s history from both in front of and behind the cameras, and chats to them about their time working on Doctor Who and the lives they have led since (and, indeed, before).

The interviews are in the form of podcasts on the Big Finish website, which you can download or stream here, or subscribe on iTunes, Spotify or other podcast outlets. All episodes are free, so if you’ve enjoyed Toby’s chat, all he asks is that you give a donation to a charity nominated by the interview subject.

Una is a New York Times bestselling science fiction author. She is passionate about women’s writing, science fiction, and helping people find their words and voices. Her work includes Doctor Who novels and Doctor Who stories for Big Finish eg Red Planets as well as Star Trek novels and other work.

Univerity of Liverpool; Science fiction collection.

The book stock at Liverpool is mainly formed by the Science Fiction Foundation Library. It represents the largest catalogued collection of science fiction, fantasy, horror and related literary criticism in Europe, totalling over 35,000 books.

Run by sisters Katie and Claire and devoted to their varied interests, including Hartnell era Doctor Who.

Put simply Ursula was the most influential science fiction writer of the past half century.

“A Doctor Who podcast where a rotating cast of six women, from across the globe, talk all things Doctor Who. We have opinions.”

Adam Roberts read through the whole of HG Wells’ work for a book and blogged about each book as he went along. The book H G Wells, A Literary Life, was published by Palgrave.

The work of Lisa Yaszek

“A grim fantasy” : remaking American history in Octavia Butler’s Kindred

Women’s Press Science Fiction series

Between 1983 and 1990 the Women’s Press published a series of feminist science fiction novels and collections by women writers. The titles included a mix of classsics and new work. Some bear rereading, some less so.

You can read reviews I have written of a number of the novels here.

You can read more about the series here – SF Mistressworks website

This book seems to have dropped through a wormhole in the Space-Time Continuum. According to the pre-publication publicity it’s not meant to be available until 18 January 2018, but I found it last week on the shelf at Manchester Central Reference Library.

This book seems to have dropped through a wormhole in the Space-Time Continuum. According to the pre-publication publicity it’s not meant to be available until 18 January 2018, but I found it last week on the shelf at Manchester Central Reference Library. “The Ambassadors of Death” is perhaps Malcolm Hulke’s least satisfactory contribution to Doctor Who. Originally called “The Carriers of Death,” the serial started life as a commission for David Whitaker in 1968. Whitaker was Doctor Who‘s first story editor, overseeing some 51 episodes in the series’ first year. He also wrote a number of serials, including “The Crusade” (1965), “The Power of the Daleks” (1966) and “The Wheel in Space” (1968).

“The Ambassadors of Death” is perhaps Malcolm Hulke’s least satisfactory contribution to Doctor Who. Originally called “The Carriers of Death,” the serial started life as a commission for David Whitaker in 1968. Whitaker was Doctor Who‘s first story editor, overseeing some 51 episodes in the series’ first year. He also wrote a number of serials, including “The Crusade” (1965), “The Power of the Daleks” (1966) and “The Wheel in Space” (1968). The story centres on a British spaceship Recovery Seven, sent into space to investigate what has happened to the previous Mars Probe Seven. It locates the ship, but then stops communicating. The Doctor and the Brigadier are called in, who succeed in tracing a mysterious signal sent to the Probe from Earth to a warehouse where a gun battle takes place with a number of military men commanded by a General Carrington.

The story centres on a British spaceship Recovery Seven, sent into space to investigate what has happened to the previous Mars Probe Seven. It locates the ship, but then stops communicating. The Doctor and the Brigadier are called in, who succeed in tracing a mysterious signal sent to the Probe from Earth to a warehouse where a gun battle takes place with a number of military men commanded by a General Carrington. What might have worked as a four part serial becomes quite threadbare when stretched over seven parts, leaving the viewer sufficient to time to ponder on some of the more improbable aspects of the plot. Why is the space control centre in charge of the Mars probe expedition run by just four people? If the aliens are so powerful – judging by the size of their ship – why not simply swoop down and rescue their ambassadors? Why is Reegan single-handedly able to run rings around UNIT, kidnapping and killing at will? Why is the space scientist Taltalian, who holds the Doctor and Liz Shaw at gunpoint in episode 2, allowed to carry on working there and the incident forgotten, after which he plants a bomb and tries to blow up the Doctor? And finally where did Liz Shaw buy her stylish hat?

What might have worked as a four part serial becomes quite threadbare when stretched over seven parts, leaving the viewer sufficient to time to ponder on some of the more improbable aspects of the plot. Why is the space control centre in charge of the Mars probe expedition run by just four people? If the aliens are so powerful – judging by the size of their ship – why not simply swoop down and rescue their ambassadors? Why is Reegan single-handedly able to run rings around UNIT, kidnapping and killing at will? Why is the space scientist Taltalian, who holds the Doctor and Liz Shaw at gunpoint in episode 2, allowed to carry on working there and the incident forgotten, after which he plants a bomb and tries to blow up the Doctor? And finally where did Liz Shaw buy her stylish hat? In previous posts I have looked at a number of novels by Fred Hoyle:

In previous posts I have looked at a number of novels by Fred Hoyle:

After the post-nuclear war landscape of The Chrysalids John Wyndham’s fourth novel, The Midwich Cuckoos, was a return to familiar (though, as we shall see, unsettling) territory, a possible alien invasion of the world.

After the post-nuclear war landscape of The Chrysalids John Wyndham’s fourth novel, The Midwich Cuckoos, was a return to familiar (though, as we shall see, unsettling) territory, a possible alien invasion of the world.

In a previous post I discussed

In a previous post I discussed

argued that The Kraken Wakes influenced Maclolm Hulke’s 1971 Doctor Who serial “The Sea Devils”, in which an undersea colony of Silurians – intelligent reptiles who once ruled the earth millions of years ago – are awoken and begin attacking ships, sinking them. In one episode they also come ashore to attack the coast. The Doctor tries to make peace between the Silurians and humanity – but fails, and they are destroyed. As Malcolm once said, “

argued that The Kraken Wakes influenced Maclolm Hulke’s 1971 Doctor Who serial “The Sea Devils”, in which an undersea colony of Silurians – intelligent reptiles who once ruled the earth millions of years ago – are awoken and begin attacking ships, sinking them. In one episode they also come ashore to attack the coast. The Doctor tries to make peace between the Silurians and humanity – but fails, and they are destroyed. As Malcolm once said, “