In a previous post I discussed The Day of the Triffids. In his second novel The Kraken Wakes John Wyndham again imagines the breakdown of human civilisation, but in a very different way and from a very different kind of menace. By contrast with The Day of the Triffids – in which the Triffids were home-grown destroyers and highly visible throughout the novel – in The Kraken Wakes the invaders appear to be from another planet, and are almost never seen.

In a previous post I discussed The Day of the Triffids. In his second novel The Kraken Wakes John Wyndham again imagines the breakdown of human civilisation, but in a very different way and from a very different kind of menace. By contrast with The Day of the Triffids – in which the Triffids were home-grown destroyers and highly visible throughout the novel – in The Kraken Wakes the invaders appear to be from another planet, and are almost never seen.

The story is told through the eyes of Mike and Phyllis Watson, radio journalists for the English Broadcasting Company, whose profession means – conveniently for the narrative – that they are either present at some of the key events or are in touch with the scientists or military officers trying to make sense of what is happening. It’s quite clear that Phyllis, like Josella in The Day of the Triffids, is the sharper, more prescient, of the couple, and also has a greater imagination than Mike, who comes across a stolid man of the 1950s: he probably wears a tweed jacket.

The story is spread over several years as the menace and terror escalate a little at a time: in fact the three chapters are titled Phase One, Phase Two and Phase Three. Phase One begins with Mike and Phyllis taking their honeymoon on a cruise ship from which, nearing the Azores, they observe five fuzzy red fireballs landing in the ocean and disappearing. After reporting this when they get back home they learn that there have been similar sightings around the world and that the sea sectors in which the fireballs land correlate with the deepest parts of the ocean. The Watsons are invited to join a Royal Navy expedition to investigate which lowers two men in a bathyscope, equipped with cameras. Finding nothing in the depths, they think that they see something as they ascend to the surface, as Mike Watson relates:

This time we could undoubtedly make out a lighter patch. It was roughly oval, but indistinct, and there was nothing to give it scale….Again the camera showed us a glimpse of the thing as it passed one of the bathyscope’s ports, but we were little wiser; the definition too poor for us to be sure of anything about it. “It’s going up now. Rising faster than we are. Getting beyond our angle of view. ought to be a window in the top of this thing…Lost it now. Gone somewhere up above above us. Maybe it’ll –“ The voice cut off dead. Simultaneously, there was a brief, vivid flash on the screen, and it too went dead.The sound of the winch outside altered as it speeded up….At last, the end came up…Both the main and the communications cables ended in a blob of fused metal.

After this incident shipping starts to sink and the powers-that-be decide to drop an atomic bomb into the ocean near the Marianas, but with no effect. At this point Wyndham introduces Dr Alastair Bocker into the narrative, whose analyses and predictictions are invariably derided by conventional scientific and political opinion, but usually turn out to be correct. Wyndham uses him to play a similar role to that of Michael Beadley in The Day of the Triffids. Bocker suggests that the intelligences in the deep have come from another planet, possibly Jupiter, and that an invasion is under way. He also suggests that the discolouration of the ocean, which has started happening, is caused by the intelligences drilling communication routes between the various ocean deeps.

In Phase Two a string of ocean going passenger liners are sunk with the loss of all passengers, forcing the authorities to acknowledge the reality of the deep-sea menace, which the public now reluctantly accepts, having been inclined to blame the Russians up to now. (This novel was written during the Cold War, remember). “Back room boffins” eventually come up with anti-attack devices, which when fitted to ships deal with this particular threat, but it’s far from over. Soon reports come in of mysterious raids on remote islands in which the population vanishes: all that can be found are tracks leading to and from the sea and slime covering the ground and buildings. Mike and Phyllis go off on a expedition, led by Bocker, to an island called Escondida where he predicts the next raid may take place. Nothing happens for several weeks and the group takes it easy, enjoying the sunshine. Then it starts.

What follows is one of the most horrific episodes in modern science fiction as Wyndham presents us with grey metal “sea-tanks”, some 35 feet long, which grind their way out of the sea and into the town square. They then release white cilia, sticky tentacles, which ensnare the fleeing crowd. Phyllis physically stops Mike from going out (almost certainly saving his life), so he watches from a window:

The thing that had burst was no longer in the air. It was now a round body no more than a couple of feet in diameter surrounded by a radiation of cilia. It was drawing these back into itself with whatever they had caught, and the tension was keeping it a little off the ground. Some of the people it was pulling were shouting and struggling, others were like inert bundles of clothes.

I saw poor Muriel Flynn among them. She was lying on her back, dragged across the cobbles by a tentacle caught in her red hair. She had been badly hurt by the fall when she was pulled out of her window, and was crying out with terror, too. Leslie dragged alongside her, but it looked as if the fall had mercifully broken his neck.

Over on the far side I saw a man rush forward and try to pull a screaming woman away, but when he touched the cillium that held her hand his hand became fastened to it, too, and they were dragged along.

As the circle contracted, the white cilia came closer to one another. The struggling people inevitably touched more of them and became more helplessly enmeshed than before. There was a relentless deliberation about it which made it seem horribly as though one watched through the eye of a slow-motion camera. ..the machines…still lay where they had stopped, looking like huge grey slugs, each engaged in producing several of its disgusting bubbles at different stages. …I looked out again. Half a dozen objects, looking like tight round bales, were rolling over and over on their way to the street that led to the waterfront.

After this the raids increase to a full onslaught on coasts around the world with hundreds of “sea-tanks” causing thousands of deaths. However the machines (if that is truly what they are) are vulnerable to explosive shells, and eventually they are held at bay by a combination of mines, weaponry and an alert public:

It was the Irish who took almost the whole weight of the north-European attack, which was conducted, according to Bocker, from a base somewhere in the Deep, south of Rockall. They rapidly developed a skill in dealing with them that made it a point of dishonour that even one should get away…England’s only raids occurred in Cornwall, and they too were small affairs for the most part.

The raids cease but, as Bocker prophesies in a radio broadcast, “These things, whatever they may be, have not only succeeeded in throwing us out of their element with ease, but already they have advanced to do battle with us in ours. For the moment we have pushed them back, but they will return, for the same urge drives them as drives us – the neccessity to exterminate, or be exterminated. And when they come again , if we let them, they will come better equipped…”

In Phase Three the intelligences succeed in melting the Arctic and Antarctic polar ice, and water levels around the globe start to rise rapidly. As London is progressively flooded the government flees to Harrogate. Mike and Phyllis stay on in the capital to broadcast from an EBC studio until conditions become impossible. By now the government has ceased broadcasting, and the country has balkanised into a series of armed enclaves of desperate people, ready and willing to shoot at others seeking safety and food. The Watsons manage to find a boat and, after a number of adventures, make their way to their cottage in Cornwall, where Phyllis, with her usual foresight, has laid in stocks of food.

Some months later they learn from a neighbour that their names have been broadcast by Bocker, who is part of a Council for Reconstruction. He wants them to go London to help in the business of rebuilding a post-deluge society. What about the inteligences? According to Bocker, scientists have succeeded at last in building an ultra-sound weapon that is being used to systematically to kill them and clear the deeps. The last words in the novel go to Phyllis, wise as ever:

I was just thinking…Nothing is really new, is it, Mike? Once upon a time there was a great plain, covered with forests and full of wild animals. I expect our ancestors hunted there. Then one day the water came and drowned it all and there was the North Sea…I think we’ve been here before, Mike…and and we got through last time.

Stories about what might lurk in the sea and one day rise to the surface are part of folk-culture and go back centuries. Wyndham successfully plays on these primitive fears in what is a deftly plotted story, driven by the narrative, which slowly rachets up the tension. He also subverts the conventional alien invasion novel in which “they” crash to earth and set about the violent destruction of humanity. In The Kraken Wakes “they” arrive silently and stealthily: in fact we are never quite clear whether this is really an invasion at all; are the intelligences simply seeking a new home in the deeps, but are then forced to deal with the intrusive behaviour of humanity who will not leave them alone?

In the end it seems the planet cannot be shared, a conclusion that even the humanitarian Bocker is forced to accept. The idea of the aliens “shrimping” human beings in their sea raids, as Phyllis graphically puts it, is surely a nod by Wyndham to Wells’ The War of the Worlds in which the Martians’ war machines use their ” long, flexible, glittering tentacles” to harvest human beings and put them in a basket to be later used, as Wells hints, for some ghastly alien purpose.

As in The Day of the Triffids, Wyndham cannot resist some social satire, poking fun at the fickleness of public opinion which demands immediate action, any action, to solve a perceived problem, and the stock responses of the press:

The news of the latest sinking was announced on the 8am news bulletin on a Saturday. The Sunday papers took full advantage of their opportunity. At least six of them slashed at official incompetence with almost eighteenth-century gusto, and set the pitch for the Dailies. The Times screwed down rebukes to make the juice run out. The Guardian’s approach was similar in intention, but more like an advancing set of circular-saws in manner…The Worker, after pointing out that in a properly ordered society such tragedies would have been impossible since luxury liners would not exist and therefore could not be sunk, rounded upon owners who drove seamen into danger in unprotected ships at inadequate wages.

It can plausibly be  argued that The Kraken Wakes influenced Maclolm Hulke’s 1971 Doctor Who serial “The Sea Devils”, in which an undersea colony of Silurians – intelligent reptiles who once ruled the earth millions of years ago – are awoken and begin attacking ships, sinking them. In one episode they also come ashore to attack the coast. The Doctor tries to make peace between the Silurians and humanity – but fails, and they are destroyed. As Malcolm once said, “What you need for science fiction is a good original idea. It doesn’t have to be your original idea.” You can read my post on the work of Malcolm Hulke here.

argued that The Kraken Wakes influenced Maclolm Hulke’s 1971 Doctor Who serial “The Sea Devils”, in which an undersea colony of Silurians – intelligent reptiles who once ruled the earth millions of years ago – are awoken and begin attacking ships, sinking them. In one episode they also come ashore to attack the coast. The Doctor tries to make peace between the Silurians and humanity – but fails, and they are destroyed. As Malcolm once said, “What you need for science fiction is a good original idea. It doesn’t have to be your original idea.” You can read my post on the work of Malcolm Hulke here.

Productions

It is surprising that The Kraken Wakes has never been filmed or produced as a television series, since it offers a great deal of dramatic incident, while the melting of the icecaps chimes with contemporary concerns over global warming.

The novel has been produced as a radio series on a number of occasions.

In 1954 it was produced by Peter Watts on the Third Programme from a script by John Keir Cross. Michael Watson was played by Robert Beatty, Phyllis Watson was played by Grizelda Hervey.

In 1965 the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation broadcast an adaptation starring Sam Paine, Shirley Broderick, Michael Irwin and Derek Walston. You can listen to this here

In 1998 it was produced by Susan Roberts on Radio Four from a script by John Constable. Michael Watson was played by John Branwell, Phyllis Watson was played by Kathryn Hunt.

In 2008 it was produced by Susan Roberts on Radio Four from a script by John Constable. Michael Watson was played by Jonathan Cake, Phyllis Watson was played by Sarah Todd.

On 8 January 2016 a new adaptation, written by Val McDermid, was recorded live in Media City, Salford, with the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra. It starred Tamsin Greig, Paul Higgins and Richard Harrington. The score was composed by Alan Edward Williams. The First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, played herself in pre-recorded section. This production was broadcast on Radio Four on 28 May 2016. More information here

Finally, the title of the book comes from a poem by Tennyson, The Kraken.

Below the thunders of the upper deep,

Far, far beneath in the abysmal sea,

His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep

The Kraken sleepeth: faintest sunlights flee

About his shadowy sides; above him swell

Huge sponges of millennial growth and height;

And far away into the sickly light,

From many a wondrous grot and secret cell

Unnumbered and enormous polypi

Winnow with giant arms the slumbering green.

There hath he lain for ages, and will lie

Battening upon huge sea worms in his sleep,

Until the latter fire shall heat the deep;

Then once by man and angels to be seen,

In roaring he shall rise and on the surface die.

If you would like to comment on this post, you can either comment via the blog or email me, fopsfblog@gmail.

problems of one of Britain’s most grotesque city environments.

problems of one of Britain’s most grotesque city environments.

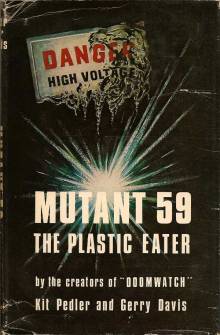

By 1970 Kit was becoming disillusioned by science and increasingly alarmed about the effect that technology and the headlong rush for economic growth at all costs was having on the environment. He, and many others around the globe, feared the possibility of ecological collapse. Working together again, Kit and Gerry created a series for the BBC called

By 1970 Kit was becoming disillusioned by science and increasingly alarmed about the effect that technology and the headlong rush for economic growth at all costs was having on the environment. He, and many others around the globe, feared the possibility of ecological collapse. Working together again, Kit and Gerry created a series for the BBC called