With the departure of Patrick Troughton in 1969 Doctor Who teetered on the edge of cancellation as the ratings had fallen to just above five million for his final ten part serial, “The War Games.” In the end the BBC decided to give it another season, which some suspected might well prove to be the last. Against the odds the series was re-invigorated, re-establishing itself as a Saturday teatime must-see for another generation of young people, including myself. This was brought about by four key factors:

Firstly, the producer Derrick Sherwin – who bridged the transition from the Second to the Third Doctor – opted for a new story arc, anchoring the Doctor on Earth (having been exiled by the Time Lords at the end of “The War Games”) where he becomes the scientific advisor to UNIT, a quasi-military outfit first encountered by the Second Doctor in “the Invasion.” UNIT is led by Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart (Nicholas Courtney) who first appeared as a regular army officer in “The Web of Fear” and then as the commanding officer of UNIT in “The Invasion”.

The programme makers felt that the format had become tired and wanted to show the Doctor battling his enemies on Earth, rather than on far distant planets. The Earth in fact turned out to be the Home Counties, subject to a surprisingly high number of alien invasions. This format harked back to the Quatermass serials of the 1950s in which Professor Bernard Quatermass also grappled with alien invasions of southern England.

Secondly, the new serials were filmed in colour, which allowed a fresh look (although it was not without problems when the screen showed less than convincing monsters and questionable sets). Of course, to begin with many people would still have watched Doctor Who in black and white as colour TV sets were very expensive to begin with: just 200,000 sets having been sold by the end of 1969. By 1976, however, over 1 million had been sold and the sales of colour sets overtook those of black and white sets.

Barry Letts and Terrance Dicks

Thirdly, the series was driven forward by the new script editor, Terrance Dicks, and the new producer, Barry Letts, who took over from Sherwin when he departed after producing the new Doctor’s first serial, “Spearhead in Space.” Letts and Dicks formed a very close professional working relationship which was instrumental in popularising Doctor Who to a fresh audience.

From the interviews they seem quite different characters: Letts the intellectual, interested in subjects such as Buddhism for instance, whilst Dicks is the practical man of television dedicated to ensuring that, as he often says, “the screen doesn’t go blank at 5.30pm”.

And finally the inspired choice of Jon Pertwee as Troughton’s replacement, whose selection was a surprise to many. Jon came from a “clan” (as he termed of it) of writers and actors. When the Second World War started he joined the Royal Navy, avoiding the RAF as, according to Jon, he had a fear of being trapped in a burning aircraft. If you look closely at his arm in some episodes you can see his naval tattoo of a scarlet and green cobra, acquired after a very drunken night out.

Jon served for a time on HMS Hood, where he was a spotter up in the spotting top. He was transferred off the ship by the Captain for officer training which was very lucky for him, for, on 24th May 1941, HMS Hood was attacked by the Bismarck and exploded within minutes with the loss of 1, 415 men. Just three crewmen survived. Jon says, “It was such a dreadful thing to happen. I lost all my friends, all of my mates. All of them…You never really escape things like that. They stay with you all of your life”.

Looking back Jon was adamant about the horrors of war:

Looking back Jon was adamant about the horrors of war:

“War is terrible. Anyone who tells you different is a liar…I realise I was very lucky to survive the war. There were a lot of times I nearly died. Once I was with some shipmates on leave in London and there was an air-raid. I had premonition and went down into the underground station to take shelter, but my shipmates wanted to get home to loved ones. …Next morning, I made my way back to my barracks, horrified by the damage done during the attack. It really was all smoke and ruins. I was the only one who got back to barracks. All of my mates had been killed during the bombing…A lot of nights it really did feel like the end of the world.” Doctor Who magazine, 457, March 2013, Interview with Jon Pertwee, p.25.

After the war Pertwee forged a career as a comic actor mainly on the radio, his most well-known role being that of Chief Officer Pertwee in The Navy Lark from 1959 to 1977 (which is still being repeated on Radio Four Extra, by the way). Jon was offered the part of Captain Mainwaring in Dad’s Army but turned it down as he was appearing on Broadway in A Girl in My Soup. When the role of the Doctor came up Jon asked his agent to apply for the role, and was surprised to find he was already on the shortlist. He was actually the second choice, Ron Moody being the first bur Moody was not available. Jon had not watched the series much before taking the role.

Jon was given a wardrobe which exactly suited his character and patrician personality, cutting an Edwardian dash in frills, velvets, hat and cape. They also gave him a retro car, Bessie. In contrast to Pat Troughton quixotic clowning, Jon is very much the action man. He often uses Venusian Akido, felling his opponents with a single touch. In “The Time Warrior” he fights the medieval knights with a sword, and even swings across the room on a chandelier, Errol Flynn style. In “The Curse of Peladon” he fights the King’s champion, Grun, in single-combat – and wins. In “Colony in Space” he fights off an attack from the Primitives who are armed with spears. The Doctor is launched into space in “The Ambassadors of Death” and goes on a space walk in “Frontier in Space”. Jon never missed an opportunity to include a gadget or some mechanised method of transport into the role.

He is also presented as a scientist. The serials often open with the Doctor sitting in a laboratory conducting an experiment or tinkering with a piece of the Tardis, as he tries to overcome the Timelords’ prohibition on his leaving the Earth. In “The Silurians” he works to find a cure for the plague spread by the Silurians. In “The Sea Devils” he rejigs a transistor radio to transmit a distress signal. In “The Time Monster” he rigs up a Heath Robinson gadget which he calls a “time flow analogue “ to interrupt the Master’s experiments with time.

The Third Doctor is an anti-authority figure, impatient with red-tape or bureaucracy, and very short-tempered with the establishment figures he comes across such as Whitehall civil servants in pin-stripes, army generals, businessmen and scientists.

There are occasional flashes of Jon’s talent for comedy. In “The Green Death” he dresses up as milk-man with a Welsh accent to infiltrate the headquarters of Global Chemicals, and later on in the same serial masquerades as a char-lady in a scene straight out of a Carry On film.

Barry Letts says: Jon was a kind and unselfish man as well; indeed, his sensitivity was extended to everyone else. He did a lot to turn our casts and crew into a cohesive and happy company. For example, when a newcomer (even playing a small part) arrived in the rehearsal room, he’d wander over and introduce himself. “Hello, I’m Jon Pertwee, I play the Doctor”. He made good friends of all the stunt men and other actors who were regularly cast. He was amusing and charming, and could surprise you with flashes of unexpected humility. Barry Letts, Who & Me (2007) , p25.

Jon was introduced as the Doctor in “Spearhead from Space,, written by Robert Holmes, probably the most influential writer in th ehistory of the series. After serving in the army during the war in Burma where he became an officer and joining the police on returning to England, he started working as journalist. He then progressed to writing for television including scripts for The Saint, Public Eye and a science fiction series, Undermind. Holmes began writing for Doctor Who, working with Terrance Dicks on “The Krotons” to fill a gap in the schedule, and then wrote “The Space Pirates”.

Jon’s companion for his first season was Caroline John, who plays a Cambridge scientist, Dr Liz Shaw. Caroline had worked mostly worked in the theatre and had struggled to get any roles on television. When she went for the interview they talked to her about The Avengers and how they wanted to make it more sophisticated with Jon Pertwee taking on the role as the Doctor.

Caroline says that when the filming started for the first serial she was “a bundle of nerves”. She recalls Jon as being totally professional and an excellent actor and says they got on very well “in a sort of father-daughter relationship”. As a character Liz is clever, self-assured, cool, not at all over-awed by the military men or male scientists with whom she is usually surrounded, and sticks up for herself when neccessary. She never gets to travel in the Tardis, however, or even see inside.

“Spearhead From Space” opens with meteorites falling to Earth, part of an invasion by the Autons, a collective intelligence, which has seized control of a plastics factory and is creating replicas in readiness to take over the Earth. At the start of the first episode the Doctor is shown falling out of the Tardis and spends much of the first and second episode in a coma, recovering from his regeneration. Meanwhile Lethbridge- Stewart has recruited Liz Shaw to advise on the scientific implications of the meteorites. The Doctor finally wakes up, escapes from hospital in borrowed clothes, steals a car and makes his way to UNIT HQ, where he convinces the Brigadier that he is indeed the Doctor, despite his new appearance.

The invasion begins when shop dummies spark to life and terrorise the high streets of England in a classic scene (although to Derrick Sherwin’s chagrin, the BBC budget did not stretch to the dummies being shown smashing their way through the shop windows). Finally the Doctor puts together a device with Liz’s help which defeats the Autons. The serial ends with the Brigadier offering the Doctor a job as their scientific advisor as “Doctor John Smith”

The invasion begins when shop dummies spark to life and terrorise the high streets of England in a classic scene (although to Derrick Sherwin’s chagrin, the BBC budget did not stretch to the dummies being shown smashing their way through the shop windows). Finally the Doctor puts together a device with Liz’s help which defeats the Autons. The serial ends with the Brigadier offering the Doctor a job as their scientific advisor as “Doctor John Smith”

Unusually “Spearhead from Space” was shot entirely on location in 16mm without the use of studio sets because there was a strike at the BBC,and the studios could not be used. This meant that the direction is fluid and dynamic (just watch the press scrum scene at the hospital), and looks great more than forty years later.

Overall it’s a great season opener and harbinger of even greater things to come. When Russell T Davies brought back Doctor Who in 2005, out of all the possible alien threats from Doctor Who’s past, he chose the Autons to appear in the very first serial, “Rose,” his tribute to a classic era of Doctor Who.

Further reading and useful links

Barry Letts, Who & Me (2007)

Richard Molesworth, Robert Holmes: A Life in Words (2013) published by Telos publishing

interview with Caroline John (1990) Wine and Dine

If you would like to comment on this post, you can either comment via the blog or email me, fopsfblog@gmail.

As an avid Doctor Who viewer since the first episode on 23rd November 1963 I almost certainly watched “The Macra Terror”, aged 11, on its original broadcast March to April 1967, but I have no recollection of it whatsover. Which means that I got to this watch the serial as though I was seeing it for the first time which was a real pleasure.

As an avid Doctor Who viewer since the first episode on 23rd November 1963 I almost certainly watched “The Macra Terror”, aged 11, on its original broadcast March to April 1967, but I have no recollection of it whatsover. Which means that I got to this watch the serial as though I was seeing it for the first time which was a real pleasure. This Doctor Who novel was a long time in coming. It began life as a joint script dreamt up by Tom Baker and his co-star, the late

This Doctor Who novel was a long time in coming. It began life as a joint script dreamt up by Tom Baker and his co-star, the late Your recent actions endangered the enture universe,” the Zero Nun informed me.

Your recent actions endangered the enture universe,” the Zero Nun informed me.

The novel opens with the Doctor and his companions landing on a remote Scottish island. (Science fiction and Scottish islands seems to naturally go together, one thinks of

The novel opens with the Doctor and his companions landing on a remote Scottish island. (Science fiction and Scottish islands seems to naturally go together, one thinks of  This is one of three novels published by the BBC which feature The Thirteenth Doctor for the first time (the other two are Combat Magicks by Steve Cole and The Good Doctor by Juno Dawson).

This is one of three novels published by the BBC which feature The Thirteenth Doctor for the first time (the other two are Combat Magicks by Steve Cole and The Good Doctor by Juno Dawson). This Doctor Who audio adventure from

This Doctor Who audio adventure from  lin, Ace finds that strange things are happening, streets are vanishing, the city is disappearing, and a deadly fog is killing people. In London the Doctor is trying to work out what has caused the change in history, “Nothing here is right,” but finds himself in the hands of people who seem to know a lot about him. And on Mars the expedition is heading for a rendezvous….with something impossible. Can the Doctor reverse history or will Mokoshia “unite the human race.”

lin, Ace finds that strange things are happening, streets are vanishing, the city is disappearing, and a deadly fog is killing people. In London the Doctor is trying to work out what has caused the change in history, “Nothing here is right,” but finds himself in the hands of people who seem to know a lot about him. And on Mars the expedition is heading for a rendezvous….with something impossible. Can the Doctor reverse history or will Mokoshia “unite the human race.” Ursula Le Guin is one of the most important science fiction writers of the twentieth century, whose works such The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossesed continue to be very influential. Ursula was an activist in the USA in the campaign against the Vietnam War, and The Word for World Is Forest clearly emerged from that experience. Much of the war was fought in forests between the Americans, who had vast military techonology, and the guerilla army of the Vietcong, who had no such weaponry, but were armed instead with an unrelenting desire to be free.

Ursula Le Guin is one of the most important science fiction writers of the twentieth century, whose works such The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossesed continue to be very influential. Ursula was an activist in the USA in the campaign against the Vietnam War, and The Word for World Is Forest clearly emerged from that experience. Much of the war was fought in forests between the Americans, who had vast military techonology, and the guerilla army of the Vietcong, who had no such weaponry, but were armed instead with an unrelenting desire to be free.

Selver co-ordinates attacks from thousands of Athsheans on the Earth settlements, killing many men and women, and setting fire to the buildings. His friend Lyubov dies in one of the attacks. Selver pens the survivors into a compound and negotiates a truce. This is broken by Davidson who organises attacks on the Athshean cities in the forest. Finally, Selver captures him alive, and tells him:

Selver co-ordinates attacks from thousands of Athsheans on the Earth settlements, killing many men and women, and setting fire to the buildings. His friend Lyubov dies in one of the attacks. Selver pens the survivors into a compound and negotiates a truce. This is broken by Davidson who organises attacks on the Athshean cities in the forest. Finally, Selver captures him alive, and tells him: “The Ambassadors of Death” is perhaps Malcolm Hulke’s least satisfactory contribution to Doctor Who. Originally called “The Carriers of Death,” the serial started life as a commission for David Whitaker in 1968. Whitaker was Doctor Who‘s first story editor, overseeing some 51 episodes in the series’ first year. He also wrote a number of serials, including “The Crusade” (1965), “The Power of the Daleks” (1966) and “The Wheel in Space” (1968).

“The Ambassadors of Death” is perhaps Malcolm Hulke’s least satisfactory contribution to Doctor Who. Originally called “The Carriers of Death,” the serial started life as a commission for David Whitaker in 1968. Whitaker was Doctor Who‘s first story editor, overseeing some 51 episodes in the series’ first year. He also wrote a number of serials, including “The Crusade” (1965), “The Power of the Daleks” (1966) and “The Wheel in Space” (1968). The story centres on a British spaceship Recovery Seven, sent into space to investigate what has happened to the previous Mars Probe Seven. It locates the ship, but then stops communicating. The Doctor and the Brigadier are called in, who succeed in tracing a mysterious signal sent to the Probe from Earth to a warehouse where a gun battle takes place with a number of military men commanded by a General Carrington.

The story centres on a British spaceship Recovery Seven, sent into space to investigate what has happened to the previous Mars Probe Seven. It locates the ship, but then stops communicating. The Doctor and the Brigadier are called in, who succeed in tracing a mysterious signal sent to the Probe from Earth to a warehouse where a gun battle takes place with a number of military men commanded by a General Carrington. What might have worked as a four part serial becomes quite threadbare when stretched over seven parts, leaving the viewer sufficient to time to ponder on some of the more improbable aspects of the plot. Why is the space control centre in charge of the Mars probe expedition run by just four people? If the aliens are so powerful – judging by the size of their ship – why not simply swoop down and rescue their ambassadors? Why is Reegan single-handedly able to run rings around UNIT, kidnapping and killing at will? Why is the space scientist Taltalian, who holds the Doctor and Liz Shaw at gunpoint in episode 2, allowed to carry on working there and the incident forgotten, after which he plants a bomb and tries to blow up the Doctor? And finally where did Liz Shaw buy her stylish hat?

What might have worked as a four part serial becomes quite threadbare when stretched over seven parts, leaving the viewer sufficient to time to ponder on some of the more improbable aspects of the plot. Why is the space control centre in charge of the Mars probe expedition run by just four people? If the aliens are so powerful – judging by the size of their ship – why not simply swoop down and rescue their ambassadors? Why is Reegan single-handedly able to run rings around UNIT, kidnapping and killing at will? Why is the space scientist Taltalian, who holds the Doctor and Liz Shaw at gunpoint in episode 2, allowed to carry on working there and the incident forgotten, after which he plants a bomb and tries to blow up the Doctor? And finally where did Liz Shaw buy her stylish hat?

In episode two, as UNIT head to the caves equipped with small arms and grenades, the Doctor comments to his companion Liz Shaw,“That’s typical of the military mind, isn’t it? Present them with a new problem and they start shooting at it” adding “It’s not the only way you know, blasting away at things.”

In episode two, as UNIT head to the caves equipped with small arms and grenades, the Doctor comments to his companion Liz Shaw,“That’s typical of the military mind, isn’t it? Present them with a new problem and they start shooting at it” adding “It’s not the only way you know, blasting away at things.” In episode six, as the Doctor races to find a cure for the plague, he is still hoping for a peaceful outcome, pleading that “at all costs we must avoid a pitched battle.” In the seventh and final episode the Doctor tells the Brigadier that he wants to revive the Silurians one at a time, “there is a wealth of scientific knowledge down here..and I can’t wait to get started on it.”. But unknown to the Doctor , UNIT has planted explosives which detonate as he and Liz look across the moor.

In episode six, as the Doctor races to find a cure for the plague, he is still hoping for a peaceful outcome, pleading that “at all costs we must avoid a pitched battle.” In the seventh and final episode the Doctor tells the Brigadier that he wants to revive the Silurians one at a time, “there is a wealth of scientific knowledge down here..and I can’t wait to get started on it.”. But unknown to the Doctor , UNIT has planted explosives which detonate as he and Liz look across the moor. Finally the Doctor’s companion Liz has been given a bit of a makeover from “Spearhead from Space”, no longer quite as prim and proper, now sporting fashionable short skirts and longer hair. She is often the only woman in a world of men – soldiers, scientists, civil servants etc – who frequently patronise her, and she has to assert herself. In episode two she objects to being left behind when the rest of them head off to the caves, asking the Brigadier, “Have you never heard of women’s emancipation?” In episode four she does go into the caves with the Doctor. In episode six , when the Brigadier asks her to man the phones Liz snaps back, “I am scientist, not an office boy.” In 1970 the

Finally the Doctor’s companion Liz has been given a bit of a makeover from “Spearhead from Space”, no longer quite as prim and proper, now sporting fashionable short skirts and longer hair. She is often the only woman in a world of men – soldiers, scientists, civil servants etc – who frequently patronise her, and she has to assert herself. In episode two she objects to being left behind when the rest of them head off to the caves, asking the Brigadier, “Have you never heard of women’s emancipation?” In episode four she does go into the caves with the Doctor. In episode six , when the Brigadier asks her to man the phones Liz snaps back, “I am scientist, not an office boy.” In 1970 the

Looking back Jon was adamant about the horrors of war:

Looking back Jon was adamant about the horrors of war:

The invasion begins when shop dummies spark to life and terrorise the high streets of England in a classic scene (although to Derrick Sherwin’s chagrin, the BBC budget did not stretch to the dummies being shown smashing their way through the shop windows). Finally the Doctor puts together a device with Liz’s help which defeats the Autons. The serial ends with the Brigadier offering the Doctor a job as their scientific advisor as “Doctor John Smith”

The invasion begins when shop dummies spark to life and terrorise the high streets of England in a classic scene (although to Derrick Sherwin’s chagrin, the BBC budget did not stretch to the dummies being shown smashing their way through the shop windows). Finally the Doctor puts together a device with Liz’s help which defeats the Autons. The serial ends with the Brigadier offering the Doctor a job as their scientific advisor as “Doctor John Smith”

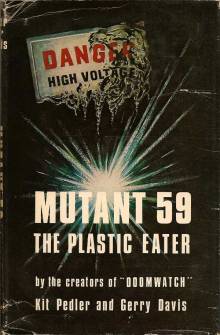

By 1970 Kit was becoming disillusioned by science and increasingly alarmed about the effect that technology and the headlong rush for economic growth at all costs was having on the environment. He, and many others around the globe, feared the possibility of ecological collapse. Working together again, Kit and Gerry created a series for the BBC called

By 1970 Kit was becoming disillusioned by science and increasingly alarmed about the effect that technology and the headlong rush for economic growth at all costs was having on the environment. He, and many others around the globe, feared the possibility of ecological collapse. Working together again, Kit and Gerry created a series for the BBC called